Topics Covered In This Chapter:

- The time module.

- The time.sleep() function.

- The return keyword.

- Creating our own functions with the def keyword.

- The and and or and not Boolean operators.

- Truth tables

- Variable scope (Global and Local)

- Parameters and Arguments

- Flow charts

Introducing Functions

We've already used two functions in our previous programs: input() and print(). In our previous programs, we have called these functions to execute the code that is inside these functions. In this chapter, we will write our own functions for our programs to call. A function is like a mini-program that is inside of our program. Many times in a program we want to run the exact same code multiple times. Instead of typing out this code several times, we can put that code inside a function and call the function several times. This has the added benefit that if we make a mistake, we only have one place in the code to change it.

The game we will create to introduce functions is called "Dragon Realm", and lets the player make a guess between two caves which randomly hold treasure or certain doom.

How to Play "Dragon Realm"

In this game, the player is in a land full of dragons. The dragons all live in caves with their large piles of collected treasure. Some dragons are friendly, and will share their treasure with you. Other dragons are greedy and hungry, and will eat anyone who enters their cave. The player is in front of two caves, one with a friendly dragon and the other with a hungry dragon. The player is given a choice between the two.

Open a new file editor window by clicking on the menu, then click on . In the blank window that appears type in the source code and save the source code as dragon.py. Then run the program by pressing F5.

Sample Run of Dragon Realm

You are in a land full of dragons. In front of you,

you see two caves. In one cave, the dragon is friendly

and will share his treasure with you. The other dragon

is greedy and hungry, and will eat you on sight.

Which cave will you go into? (1 or 2)

1

You approach the cave...

It is dark and spooky...

A large dragon jumps out in front of you! He opens his jaws and...

Gobbles you down in one bite!

Do you want to play again? (yes or no)

no

you see two caves. In one cave, the dragon is friendly

and will share his treasure with you. The other dragon

is greedy and hungry, and will eat you on sight.

Which cave will you go into? (1 or 2)

1

You approach the cave...

It is dark and spooky...

A large dragon jumps out in front of you! He opens his jaws and...

Gobbles you down in one bite!

Do you want to play again? (yes or no)

no

Dragon Realm's Source Code

Here is the source code for the Dragon Realm game. Typing in the source code is a great way to get used to the code. But if you don't want to do all this typing, you can download the source code from this book's website at the URL http://inventwithpython.com/chapter6. There are instructions on the website that will tell you how to download and open the source code file. If you type in the code yourself, you can use the online diff tool on the website to check for any mistakes in your code.

One thing to know as you read through the code below: The blocks that follow the def lines define a function, but the code in that block does not run until the function is called. The code does not execute each line in this program in top down order. This will be explained in more detail later in this chapter.

Important Note! Be sure to run this program with Python 3, and not Python 2. The programs in this book use Python 3, and you'll get errors if you try to run them with Python 2. You can click on and then to find out what version of Python you have.

dragon.py

This code can be downloaded from http://inventwithpython.com/dragon.py

If you get errors after typing this code in, compare it to the book's code with the online diff tool at http://inventwithpython.com/diff or email the author at al@inventwithpython.com

This code can be downloaded from http://inventwithpython.com/dragon.py

If you get errors after typing this code in, compare it to the book's code with the online diff tool at http://inventwithpython.com/diff or email the author at al@inventwithpython.com

- import random

- import time

- def displayIntro():

- print('You are in a land full of dragons. In front of you,')

- print('you see two caves. In one cave, the dragon is friendly')

- print('and will share his treasure with you. The other dragon')

- print('is greedy and hungry, and will eat you on sight.')

- print()

- def chooseCave():

- cave = ''

- while cave != '1' and cave != '2':

- print('Which cave will you go into? (1 or 2)')

- cave = input()

- return cave

- def checkCave(chosenCave):

- print('You approach the cave...')

- time.sleep(2)

- print('It is dark and spooky...')

- time.sleep(2)

- print('A large dragon jumps out in front of you! He opens his jaws and...')

- print()

- time.sleep(2)

- friendlyCave = random.randint(1, 2)

- if chosenCave == str(friendlyCave):

- print('Gives you his treasure!')

- else:

- print('Gobbles you down in one bite!')

- playAgain = 'yes'

- while playAgain == 'yes' or playAgain == 'y':

- displayIntro()

- caveNumber = chooseCave()

- checkCave(caveNumber)

- print('Do you want to play again? (yes or no)')

- playAgain = input()

How the Code Works

Let's look at the source code in more detail.

- import random

- import time

Here we have two import statements. We import the random module like we did in the Guess the Number game. In Dragon Realm, we will also want some time-related functions that the time module includes, so we will import that as well.

Defining the displayIntro() Function

- def displayIntro():

- print('You are in a land full of dragons. In front of you,')

- print('you see two caves. In one cave, the dragon is friendly')

- print('and will share his treasure with you. The other dragon')

- print('is greedy and hungry, and will eat you on sight.')

- print()

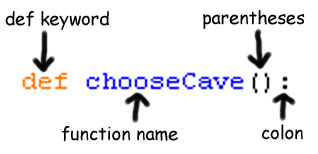

Figure 6-1: Parts of a def statement.

Figure 6-1 shows a new type of statement, the def statement. The def statement is made up of the def keyword, followed by a function name with parentheses, and then a colon (the : sign). There is a block after the statement called the def-block.

|

def Statements

The def statement isn't a call to a function named displayIntro(). Instead, the def statement means we are creating, or defining, a new function that we can call later in our program. After we define this function, we can call it the same way we call other functions. When we call this function, the code inside the def-block will be executed.

We also say we define variables when we create them with an assignment statement. The code spam = 42 defines the variable spam.

Remember, the def statement doesn't execute the code right now, it only defines what code is executed when we call the displayIntro() function later in the program. When the program's execution reaches adef statement, it skips down to the end of the def-block. We will jump back to the top of the def-block when the displayIntro() function is called. It will then execute all the print() statements inside the def-block. So we call this function when we want to display the "You are in a land full of dragons..." introduction to the user.

When we call the displayIntro() function, the program's execution jumps to the start of the function on line 5. When the function's block ends, the program's execution returns to the line that called the function.

We will explain all of the functions that this program will use before we explain the main part of the program. It may be a bit confusing to learn the program out of the order that it executes. But just keep in mind that when we define the functions they just silently sit around waiting to be called into action.

Defining the chooseCave() Function

- def chooseCave():

Here we are defining another function called chooseCave. The code in this function will prompt the user to select which cave they should go into.

- cave = ''

- while cave != '1' and cave != '2':

Inside the chooseCave() function, we create a new variable called cave and store a blank string in it. Then we will start a while loop. This while statement's condition contains a new operator we haven't seen before called and. Just like the - or * are mathematical operators, and == or != are comparison operators, the and operator is a Boolean operator.

Boolean Operators

Boolean logic deals with things that are either true or false. This is why the Boolean data type only has two values, True and False. Boolean expressions are always either True or False. If the expression is notTrue, then it is False. And if the expression is not False, then it is True.

Boolean operators compare two Boolean values (also called bools) and evaluate to a single Boolean value. Do you remember how the * operator will combine two integer values and produce a new integer value (the product of the two original integers)? And do you also remember how the + operator can combine two strings and produce a new string value (the concatenation of the two original strings)? The and Boolean operator combines two Boolean values to produce a new Boolean value. Here's how the and operator works.

Think of the sentence, "Cats have whiskers and dogs have tails." This sentence is true, because "cats have whiskers" is true and "dogs have tails" is also true.

But the sentence, "Cats have whiskers and dogs have wings" would be false. Even though "cats have whiskers" is true, dogs do not have wings, so "dogs have wings" is false. The entire sentence is only true if both parts are true because the two parts are connected by the word "and." If one or both parts are false, then the entire sentence is false.

The and operator in Python works this way too. If the Boolean values on both sides of the and keyword are True, then the expression with the and operator evaluates to True. If either of the Boolean values areFalse, or both of the Boolean values are False, then the expression evaluates to False.

Evaluating an Expression That Contains Boolean Operators

So let's look at line 13 again:

- while cave != '1' and cave != '2':

This condition is has two expressions connected by the and Boolean operator. We first evaluate these expressions to get their Boolean (that is, True or False) values. Then we evaluate the Boolean values with theand operator.

The string value stored in cave when we first execute this while statement is the blank string, ''. The blank string does not equal the string '1', so the left side evaluates to True. The blank string also does not equal the string '2', so the right side evaluates to True. So the condition then turns into True and True. Because both Boolean values are True, the condition finally evaluates to True. And because the whilestatement's condition is True, the program execution enters the while-block.

This is all done by the Python interpreter, but it is important to understand how the interpreter does this. This picture shows the steps of how the interpreter evaluates the condition (if the value of cave is the blank string):

while cave != '1' and cave != '2':

while '' != '1' and cave != '2':

while True and cave != '2':

while True and '' != '2':

while True and True:

while True:

while '' != '1' and cave != '2':

while True and cave != '2':

while True and '' != '2':

while True and True:

while True:

Experimenting with the and and or Operators

Try typing the following into the interactive shell:

>>> True and True

True

>>> True and False

False

>>> False and True

False

>>> False and False

False

True

>>> True and False

False

>>> False and True

False

>>> False and False

False

There are two other Boolean operators. The next one is the or operator. The or operator works similar to the and, except it will evaluate to True if either of the two Boolean values are True. The only time the oroperator evaluates to False is if both of the Boolean values are False.

The sentence "Cats have whiskers or dogs have wings." is true. Even though dogs don't have wings, when we say "or" we mean that one of the two parts is true. The sentence "Cats have whiskers or dogs have tails." is also true. (Most of the time when we say "this or that", we mean one thing is true but the other thing is false. In programming, "or" means that either of the things are true, or maybe both of the things are true.)

Try typing the following into the interactive shell:

>>> True or True

True

>>> True or False

True

>>> False or True

True

>>> False or False

False

True

>>> True or False

True

>>> False or True

True

>>> False or False

False

Experimenting with the not Operator

The third Boolean operator is not. The not operator is different from every other operator we've seen before, because it only works on one value, not two. There is only value on the right side of the not keyword, and none on the left. The not operator will evaluate to True as False and will evaluate False as True.

Try typing the following into the interactive shell:

>>> not True

False

>>> not False

True

>>> True not

SyntaxError: invalid syntax (<pyshell#0>, line 1)

False

>>> not False

True

>>> True not

SyntaxError: invalid syntax (<pyshell#0>, line 1)

Notice that if we put the Boolean value on the left side of the not operator results in a syntax error.

We can use both the and and not operators in a single expression. Try typing True and not False into the shell:

>>> True and not False

True

True

Normally the expression True and False would evaluate to False. But the True and not False expression evaluates to True. This is because not False evaluates to True, which turns the expression into True and True, which evaluates to True.

Truth Tables

If you ever forget how the Boolean operators work, you can look at these charts, which are called truth tables:

| A | and | B | is | Entire statement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | and | True | is | True |

| True | and | False | is | False |

| False | and | True | is | False |

| False | and | False | is | False |

| A | or | B | is | Entire statement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | or | True | is | True |

| True | or | False | is | True |

| False | or | True | is | True |

| False | or | False | is | False |

| not A | is | Entire statement |

|---|---|---|

| not True | is | False |

| not False | is | True |

Getting the Player's Input

- while cave != '1' and cave != '2':

- print('Which cave will you go into? (1 or 2)')

- cave = input()

On line 14 the player is asked to enter which cave they chose to enter by typing in 1 or 2 and hitting Enter. Whatever string the player typed will be stored in cave. After this code is executed, we jump back to the top of the while statement and recheck the condition. Remember that the line was:

If this condition evaluates to True, we will enter the while-block again and ask the player for a cave number to enter. But if the player typed in 1 or 2, then the cave value will either be '1' or '2'. This causes the condition to evaluate to False, and the program execution will continue on past the while loop.

The reason we have a loop here is because the player may have typed in 3 or 4 or HELLO. Our program doesn't make sense of this, so if the player did not enter 1 or 2, then the program loops back and asks the player again. In fact, the computer will patiently ask the player for the cave number over and over again until the player types in 1 or 2. When the player does that, the while-block's condition will be False, and we will jump down past the while-block and continue with the program.

Return Values

- return cave

This is the return keyword, which only appears inside def-blocks. Remember how the input() function returns the string value that the player typed in? Or how the randint() function will return a random integer value? Our function will also return a value. It returns the string that is stored in cave.

This means that if we had a line of code like spam = chooseCave(), the code inside chooseCave() would be executed and the function call will evaluate to chooseCave()'s return value. The return value will either be the string '1' or the string '2'. (Our while loop guarantees that chooseCave() will only return either '1' or '2'.)

The return keyword is only found inside def-blocks. Once the return statement is executed, we immediately jump out of the def-block. (This is like how the break statement will make us jump out of a while-block.) The program execution moves back to the line that had called the function.

You can also use the return keyword by itself just to break out of the function, just like the break keyword will break out of a while loop.

Variable Scope

Just like the values in our program's variables are forgotten after the program ends, variables created inside the function are forgotten after the execution leaves the function. Not only that, but when execution is inside the function, we cannot change the variables outside of the function, or variables inside other functions. The variable's scope is this range that variables can be modified in. The only variables that we can use inside a function are the ones we create inside of the function (or the parameter variables, described later). That is, the scope of the variable is inside in the function's block. The scope of variables created outside of functions is outside of all functions in the program.

Not only that, but if we have a variable named spam created outside of a function, and we create a variable named spam inside of the function, the Python interpreter will consider them to be two separate variables. That means we can change the value of spam inside the function, and this will not change the spam variable that is outside of the function. This is because these variables have different scopes, the global scope and the local scope.

Global Scope and Local Scope

We have names for these scopes. The scope outside of all functions is called the global scope. The scope inside of a function is called the local scope. The entire program has only one global scope, and each function has a local scope of its own. Scopes are also called namespaces.

Variables defined in the global scope can be read outside and inside functions, but can only be modified outside of all functions. Variables defined in a function's local scope can only be read or modified inside that function.

Specifically, we can read the value of global variables from the local scope, but attempting to change the value in a global variable from the local scope will leave the global variable unchanged. What Python actually does is create a local variable with the same name as the global variable. But Python will consider these to be two different variables.

Also, global variables cannot be read from a local scope if you modify that variable inside the local scope. For example, if you had a variable named spam in the global scope but also modified a variable named spam in the local scope (say, with an assignment statement) then the name "spam" can only refer to the local scope variable.

Look at this example to see what happens when you try to change a global variable from inside a local scope. Remember that the code in the funky() function isn't run until the funky() function is called. The comments explain what is going on:

# This block doesn't run until funky() is called:

def funky():

# We create a local variable named "spam"

# instead of changing the value of the global

# variable "spam":

spam = 99

# The name "spam" now refers to the local

# variable only for the rest of this

# function:

print(spam) # 99

# A global variable named "spam":

spam = 42

print(spam) # 42

# Call the funky() function:

funky()

# The global variable was not changed in funky():

print(spam) # 42

def funky():

# We create a local variable named "spam"

# instead of changing the value of the global

# variable "spam":

spam = 99

# The name "spam" now refers to the local

# variable only for the rest of this

# function:

print(spam) # 99

# A global variable named "spam":

spam = 42

print(spam) # 42

# Call the funky() function:

funky()

# The global variable was not changed in funky():

print(spam) # 42

When run, this code will output the following:

42

99

42

99

42

It is important to know when a variable is defined because that is how we know the variable's scope. A variable is defined the first time we use it in an assignment statement. When the program first executes the line:

- cave = ''

...the variable cave is defined.

If we call the chooseCave() function twice, the value stored in the variable the first time won't be remember the second time around. This is because when the execution left the chooseCave() function (that is, left chooseCave()'s local scope), the cave variable was forgotten and destroyed. But it will be defined again when we call the function a second time because line 12 will be executed again.

The important thing to remember is that the value of a variable in the local scope is not remembered in between function calls.

Defining the checkCave() Function

- def checkCave(chosenCave):

Now we are defining yet another function named checkCave(). Notice that we put the text chosenCave in between the parentheses. The variable names in between the parentheses are called parameters.

Remember, for some functions like for the str() or randint(), we would pass an argument in between the parentheses:

>>> str(5)

'5'

>>> random.randint(1, 20)

14

'5'

>>> random.randint(1, 20)

14

When we call checkCave(), we will also pass one value to it as an argument. When execution moves inside the checkCave() function, a new variable named chosenCave will be assigned this value. This is how we pass variable values to functions since functions cannot read variables outside of the function (that is, outside of the function's local scope).

Parameters are local variables that get defined when a function is called. The value stored in the parameter is the argument that was passed in the function call.

Parameters

For example, here is a short program that demonstrates parameters. Imagine we had a short program that looked like this:

def sayHello(name):

print('Hello, ' + name)

print('Say hello to Alice.')

fizzy = 'Alice'

sayHello(fizzy)

print('Do not forget to say hello to Bob.')

sayHello('Bob')

print('Hello, ' + name)

print('Say hello to Alice.')

fizzy = 'Alice'

sayHello(fizzy)

print('Do not forget to say hello to Bob.')

sayHello('Bob')

If we run this program, it would look like this:

Say hello to Alice.

Hello, Alice

Do not forget to say hello to Bob.

Hello, Bob

Hello, Alice

Do not forget to say hello to Bob.

Hello, Bob

This program calls a function we have created, sayHello() and first passes the value in the fizzy variable as an argument to it. (We stored the string 'Alice' in fizzy.) Later, the program calls thesayHello() function again, passing the string 'Bob' as an argument.

The value in the fizzy variable and the string 'Bob' are arguments. The name variable in sayHello() is a parameter. The difference between arguments and parameters is that arguments are the values passed in a function call, and parameters are the local variables that store the arguments. It might be easier to just remember that the thing in between the parentheses in the def statement is an parameter, and the thing in between the parentheses in the function call is an argument.

We could have just used the fizzy variable inside the sayHello() function instead of using a parameter. (This is because the local scope can still see variables in the global scope.) But then we would have to remember to assign the fizzy variable a string each time before we call the sayHello() function. Parameters make our programs simpler. Look at this code:

def sayHello():

print('Hello, ' + fizzy)

print('Say hello to Alice.')

fizzy = 'Alice'

sayHello()

print('Do not forget to say hello to Bob.')

sayHello()

print('Hello, ' + fizzy)

print('Say hello to Alice.')

fizzy = 'Alice'

sayHello()

print('Do not forget to say hello to Bob.')

sayHello()

When we run this code, it looks like this:

Say hello to Alice.

Hello, Alice

Do not forget to say hello to Bob.

Hello, Alice

Hello, Alice

Do not forget to say hello to Bob.

Hello, Alice

This program's sayHello() function does not have a parameter, but uses the global variable fizzy directly. Remember that you can read global variables inside of functions, you just can't modify the value stored in the variable.

Without parameters, we have to remember to set the fizzy variable before calling sayHello(). In this program, we forgot to do so, so the second time we called sayHello() the value of fizzy was still'Alice'. Using parameters instead of global variables makes function calling simpler to do, especially when our programs are very big and have many functions.

Where to Put Function Definitions

A function's definition (where we put the def statement and the def-block) has to come before you call the function. This is like how you must assign a value to a variable before you can use the variable. If you put the function call before the function definition, you will get an error. Look at this code:

sayGoodBye()

def sayGoodBye():

print('Good bye!')

def sayGoodBye():

print('Good bye!')

If you try to run it, Python will give you an error message that looks like this:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:\Python31\foo.py", line 1, in <module>

sayGoodBye()

NameError: name 'sayGoodBye' is not defined

File "C:\Python31\foo.py", line 1, in <module>

sayGoodBye()

NameError: name 'sayGoodBye' is not defined

To fix this, put the function definition before the function call:

def sayGoodBye():

print('Good bye!')

sayGoodBye()

print('Good bye!')

sayGoodBye()

Displaying the Game Results

Back to the game's source code:

- print('You approach the cave...')

- time.sleep(2)

We display some text to the player, and then call the time.sleep() function. Remember how in our call to randint(), the function randint() is inside the random module? In the Dragon Realm game, we also imported the time module. The time module has a function called sleep() that will pause the program for a few seconds. We pass the integer value 2 as an argument to the time.sleep() function to tell it to pause for exactly 2 seconds.

- print('It is dark and spooky...')

- time.sleep(2)

Here we print some more text and wait again for another 2 seconds. These short pauses add suspense to the game, instead of displaying all the text all at once. In our jokes program, we called the input() function to wait until the player pressed the Enter key. Here, the player doesn't have to do anything at all except wait.

- print('A large dragon jumps out in front of you! He opens his jaws and...')

- print()

- time.sleep(2)

What happens next? And how does the program decide what happens?

Deciding Which Cave has the Friendly Dragon

- friendlyCave = random.randint(1, 2)

Now we are going to have the program randomly chose which cave had the friendly dragon in it. Our call to the random.randint() function will return either the integer 1 or the integer 2, and store this value in a variable called friendlyCave.

- if chosenCave == str(friendlyCave):

- print('Gives you his treasure!')

Here we check if the integer of the cave we chose ('1' or '2') is equal to the cave randomly selected to have the friendly dragon. But wait, the value in chosenCave was a string (because input() returns strings) and the value in friendlyCave is an integer (because random.randint() returns integers). We can't compare strings and integers with the == sign, because they will always be different ('1' does not equal 1).

Comparing values of different data types with the == operator will always evaluate to False.

So we are passing friendlyCave to the str() function, which returns the string value of friendlyCave.

What the condition in this if statement is really comparing is the string in chosenCave and the string returned by the str() function. We could have also had this line instead:

if int(chosenCave) == friendlyCave:

Then the if statement's condition would compare the integer value returned by the int() function to the integer value in friendlyCave. The return value of the int() function is the integer form of the string stored in chosenCave.

If the if statement's condition evaluates to True, we tell the player they have won the treasure.

- else:

- print('Gobbles you down in one bite!')

Line 32 has a new keyword. The else keyword always comes after the if-block. The else-block that follows the else keyword executes if the condition in the if statement was False. Think of it as the program's way of saying, "If this condition is true then execute the if-block or else execute the else-block."

Remember to put the colon (the : sign) after the else keyword.

The Colon :

You may have noticed that we always place a colon at the end of if, else, while, and def statements. The colon marks the end of the statement, and tells us that the next line should be the beginning of a new block.

Where the Program Really Begins

- playAgain = 'yes'

This is the first line that is not a def statement or inside a def-block. This line is where our program really begins. The previous def statements merely defined the functions, it did not run the code inside of the functions. Programs must always define functions before the function can be called. This is exactly like how variables must be defined with an assignment statement before the variable can be used in the program.

- while playAgain == 'yes' or playAgain == 'y':

Here is the beginning of a while loop. We enter the loop if playAgain is equal to either 'yes' or 'y'. The first time we come to this while statement, we have just assigned the string value 'yes' to theplayAgain variable. That means this condition will be True.

Calling the Functions in Our Program

- displayIntro()

Here we call the displayIntro() function. This isn't a Python function, it is our function that we defined earlier in our program. When this function is called, the program execution jumps to the first line in thedisplayIntro() function on line 5. When all the lines in the function are done, the execution jumps back down to the line after this one.

- caveNumber = chooseCave()

This line also calls a function that we created. Remember that the chooseCave() function lets the player type in the cave they choose to go into. When the return cave line in this function executes, the program execution jumps back down here, and the parameter cave's value is the return value of this function. The return value is stored in a new variable named caveNumber. Then the execution moves to the next line.

- checkCave(caveNumber)

This line calls our checkCave() function with the argument of caveNumber's value. Not only does execution jump to line 20, but the value stored in caveNumber is copied to the parameter chosenCave inside the checkCave() function. This is the function that will display either 'Gives you his treasure!' or 'Gobbles you down in one bite!' depending on the cave the player chose to go in.

Asking the Player to Play Again

- print('Do you want to play again? (yes or no)')

- playAgain = input()

After the game has been played, the player is asked if they would like to play again. The variable playAgain stores the string that the user typed in. Then we reach the end of the while-block, so the program rechecks the while statement's condition: playAgain == 'yes' or playAgain == 'y'

The difference is, now the value of playAgain is equal to whatever string the player typed in. If the player typed in the string 'yes' or 'y', then we would enter the loop again at line 38.

If the player typed in 'no' or 'n' or something silly like 'Abraham Lincoln', then the while statement's condition would be False, and we would go to the next line after the while-block. But since there are no more lines after the while-block, the program terminates.

But remember, the string 'YES' is different from the string 'yes'. If the player typed in the string 'YES', then the while statement's condition would evaluate to False and the program would still terminate.

We've just completed our second game! In our Dragon Realm game, we used a lot of what we learned in the "Guess the Number" game and picked up a few new tricks as well. If you didn't understand some of the concepts in this program, then read the summary at the end of this chapter, or go over each line of the source code again, or try changing the source code and see how the program changes. In the next chapter we won't create a game, but learn how to use a feature of IDLE called the debugger. The debugger will help us figure out what is going on in our program as it is running.

We went through the source code from top to bottom. If you would like to go through the source code in the order that the execution flows, then check out the online tracing web site for this program at the URLhttp://inventwithpython.com/traces/dragon.html.

Designing the Program

Dragon Realm was a pretty simple game. The other games in this book will be a bit more complicated. It sometimes helps to write down everything you want your game or program to do before you start writing code. This is called "designing the program."

For example, it may help to draw a flow chart. A flow chart is a picture that shows every possible action that can happen in our game, and in what order. Normally we would create a flow chart before writing our program, so that we remember to write code for each thing that happens in the game. Figure 6-2 is a flow chart for Dragon Realm.

Figure 6-2: Flow chart for the Dragon Realm game.

To see what happens in the game, put your finger on the "Start" box and follow one arrow from the box to another box. Your finger is kind of like the program execution. Your finger will trace out a path from box to box, until finally your finger lands on the "End" box. As you can see, when you get to the "Check for friendly or hungry dragon" box, the program could either go to the "Player wins" box or the "Player loses" box. Either way, both paths will end up at the "Ask to play again" box, and from there the program will either end or show the introduction to the player again.

Summary

In the "Dragon Realm" game, we created our own functions that the main section of the program called. You can think of functions as mini-programs within our program. The code inside the function is run when our program calls that function. By breaking up our code into functions, we can organize our code into smaller and easier to understand sections. We can also run the same code by placing it inside of a function, instead of typing it out each time we want to run that code.

The inputs for functions are the arguments we pass when we make a function call. The function call itself evaluates to a value called the return value. The return value is the output of the function.

We also learned about variable scopes. Variables that are created inside of a function exist in the local scope, and variables created outside of all functions exist in the global scope. Code in the global scope can not make use of local variables. If a local variable has the same name as a variable in the global scope, Python considers it to be a separate variable and assigning new values to the local variable will not change the value in the global variable.

Variable scopes might seem complicated, but they are very useful for organizing functions as pieces of code that are separate from the rest of the function. Because each function has it's own local scope, we can be sure that the code in one function will not cause bugs in other functions.

All nontrivial programs use functions because they are so useful, including the rest of the games in this book. By understanding how functions work, we can save ourselves a lot of typing and make our programs easier to read later on.

0 comments:

Post a Comment