Topics Covered In This Chapter:

- Flow of execution

- Strings

- String concatenation

- Data types (such as strings or integers)

- Using IDLE to write source code.

- Saving and running programs in IDLE.

- The print() function.

- The input() function.

- Comments

- Capitalizing variables

- Case-sensitivity

That's enough of integers and math for now. Python is more than just a calculator. Now let's see what Python can do with text. In this chapter, we will learn how to store text in variables, combine text together, and display them on the screen. Many of our programs will use text to display our games to the player, and the player will enter text into our programs through the keyboard. We will also make our first program, which greets the user with the text, "Hello World!" and asks for the user's name.

Strings

In Python, we work with little chunks of text called strings. We can store string values inside variables just like we can store number values inside variables. When we type strings, we put them in between two single quotes ('), like this:

>>> spam = 'hello'

>>>

>>>

The single quotes are there only to tell the computer where the string begins and ends (and are not part of the string value).

Now, if you type spam into the shell, you should see the contents of the spam variable (the 'hello' string.) This is because Python will evaluate a variable to the value stored inside the variable (in this case, the string'Hello').

>>> spam = 'hello'

>>> spam

'hello'

>>>

>>> spam

'hello'

>>>

Strings can have almost any keyboard character in them. (Strings can't have single quotes inside of them without using escape characters. Escape characters are described later.) These are all examples of strings:

'hello'

'Hi there!'

'KITTENS'

'7 apples, 14 oranges, 3 lemons'

'Anything not pertaining to elephants is irrelephant.'

'A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away...'

'O*&#wY%*&OCfsdYO*&gfC%YO*&%3yc8r2'

'Hi there!'

'KITTENS'

'7 apples, 14 oranges, 3 lemons'

'Anything not pertaining to elephants is irrelephant.'

'A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away...'

'O*&#wY%*&OCfsdYO*&gfC%YO*&%3yc8r2'

As we did with numerical values in the previous chapter, we can also combine string values together with operators to make expressions.

String Concatenation

You can add one string to the end of another by using the + operator, which is called string concatenation. Try entering 'Hello' + 'World!' into the shell:

>>> 'Hello' + 'World!'

'HelloWorld!'

>>>

'HelloWorld!'

>>>

To keep the strings separate, put a space at the end of the 'Hello' string, before the single quote, like this:

>>> 'Hello ' + 'World!'

'Hello World!'

>>>

'Hello World!'

>>>

The + operator works differently on strings and integers because they are different data types. All values have a data type. The data type of the value 'Hello' is a string. The data type of the value 5 is an integer. The data type of the data that tells us (and the computer) what kind of data the value is.

Writing Programs in IDLE's File Editor

Until now we have been typing instructions one at a time into the interactive shell. When we write programs though, we type in several instructions and have them run all at once. Let's write our first program!

The name of the program that provides the interactive shell is called IDLE, the Interactive DeveLopement Environment. IDLE also has another part called the file editor.

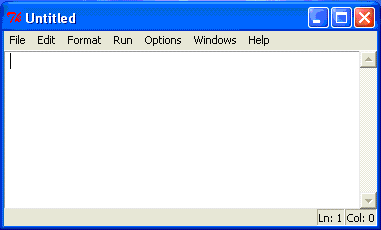

Click on the menu at the top of the Python Shell window, and select . A new blank window will appear for us to type our program in. This window is the file editor.

Figure 3-1: The file editor window.

Hello World!

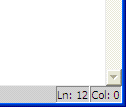

Figure 3-2: The bottom right of the file editor window tells you where the cursor is. The cursor is currently on line 12.

A tradition for programmers learning a new language is to make their first program display the text "Hello world!" on the screen. We'll create our own Hello World program now.

When you enter your program, don't enter the numbers at the left side of the code. They're there so we can refer to each line by number in our explanation. If you look at the bottom-right corner of the file editor window, it will tell you which line the cursor is currently on.

Enter the following text into the new file editor window. We call this text the program's source code because it contains the instructions that Python will follow to determine exactly how the program should behave. (Remember, don't type in the line numbers!)

IMPORTANT NOTE! The following program should be run by the Python 3 interpreter, not the Python 2.6 (or any other 2.x version). Be sure that you have the correct version of Python installed. (If you already have Python 2 installed, you can have Python 3 installed at the same time.) To download Python 3, go to http://python.org/download/releases/3.1.1/ and install this version.

|

hello.py

This code can be downloaded from http://inventwithpython.com/hello.py

If you get errors after typing this code in, compare it to the book's code with the online diff tool at http://inventwithpython.com/diff or email the author at al@inventwithpython.com

This code can be downloaded from http://inventwithpython.com/hello.py

If you get errors after typing this code in, compare it to the book's code with the online diff tool at http://inventwithpython.com/diff or email the author at al@inventwithpython.com

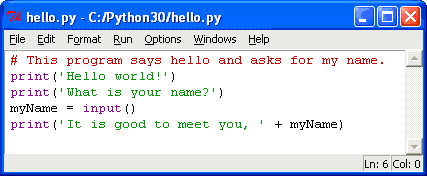

- # This program says hello and asks for my name.

- print('Hello world!')

- print('What is your name?')

- myName = input()

- print('It is good to meet you, ' + myName)

The IDLE program will give different types of instructions different colors. After you are done typing this code in, the window should look like this:

Figure 3-3: The file editor window will look like this after you type in the code.

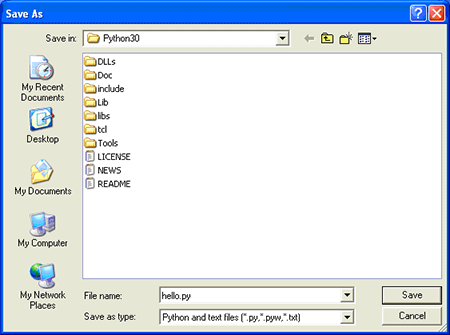

Saving Your Program

Figure 3-4: Saving the program.

Once you've entered your source code, save it so that you won't have to retype it each time we start IDLE. To do so, choose the File menu at the top of the File Editor window, and then click on . The Save As window should open. Enter hello.py in the File Name box then press . (See Figure 3-4.)

You should save your programs every once in a while as you type them. That way, if the computer crashes or you accidentally exit from IDLE, only the typing you've done since your last save will be lost. Press Ctrl-S to save your file quickly, without using the mouse at all.

|

A video tutorial of how to use the file editor is available from this book's website at http://inventwithpython.com/videos/.

If you get an error that looks like this:

Hello world!

What is your name?

Albert

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:/Python26/test1.py", line 4, in <module>

myName = input()

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'Albert' is not defined

What is your name?

Albert

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:/Python26/test1.py", line 4, in <module>

myName = input()

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'Albert' is not defined

...then this means you are running the program with Python 2, instead of Python 3. You can either install Python 3, or convert the source code in this book to Python 2. Appendix A lists the differences between Python 2 and 3 that you will need for this book.

Opening The Programs You've Saved

To load a saved program, choose . Do that now, and in the window that appears choose hello.py and press the button. Your saved hello.py program should open in the File Editor window.

Now it's time to run our program. From the File menu, choose or just press the F5 key on your keyboard. Your program should run in the shell window that appeared when you first started IDLE. Remember, you have to press F5 from the file editor's window, not the interactive shell's window.

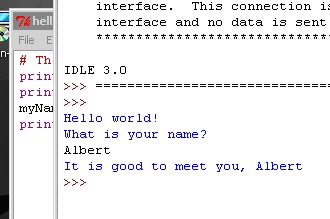

When your program asks for your name, go ahead and enter it as shown in Figure 3-5:

Figure 3-5: What the interactive shell looks like when running the "Hello World" program.

Now, when you push Enter, the program should greet you (the user) by name. Congratulations! You've written your first program. You are now a beginning computer programmer. (You can run this program again if you like by pressing F5 again.)

How the "Hello World" Program Works

How does this program work? Well, each line that we entered is an instruction to the computer that is interpreted by Python in a way that the computer will understand. A computer program is a lot like a recipe. Do the first step first, then the second, and so on until you reach the end. Each instruction is followed in sequence, beginning from the very top of the program and working down the list of instructions. After the program executes the first line of instructions, it moves on and executes the second line, then the third, and so on.

We call the program's following of instructions step-by-step the flow of execution, or just the execution for short.

Now let's look at our program one line at a time to see what it's doing, beginning with line number 1.

Comments

- # This program says hello and asks for my name.

This line is called a comment. Any text following a # sign (called the pound sign) is a comment. Comments are not for the computer, but for you, the programmer. The computer ignores them. They're used to remind you of what the program does or to tell others who might look at your code what it is that your code is trying to do.

Programmers usually put a comment at the top of their code to give their program a title. The IDLE program displays comments in red to help them stand out.

Functions

A function is kind of like a mini-program inside your program. It contains lines of code that are executed from top to bottom. Python provides some built-in functions that we can use. The great thing about functions is that we only need to know what the function does, but not how it does it. (You need to know that the print() function displays text on the screen, but you don't need to know how it does this.)

A function call is a piece of code that tells our program to run the code inside a function. For example, your program can call the print() function whenever you want to display a string on the screen. Theprint() function takes the string you type in between the parentheses as input and displays the text on the screen. Because we want to display Hello world! on the screen, we type the print function name, followed by an opening parenthesis, followed by the 'Hello world!' string and a closing parenthesis.

The print() Function

- print('Hello world!')

- print('What is your name?')

This line is a call to the print function, usually written as print() (with the string to be printed going inside the parentheses).

We add parentheses to the end of function names to make it clear that we're referring to a function named print(), not a variable named print. The parentheses at the end of the function let us know we are talking about a function, much like the quotes around the number '42' tell us that we are talking about the string '42' and not the integer 42.

Line 3 is another print() function call. This time, the program displays "What is your name?"

The input() Function

- myName = input()

This line has an assignment statement with a variable (myName) and a function call (input()). When input() is called, the program waits for input; for the user to enter text. The text string that the user enters (your name) becomes the function's output value.

Like expressions, function calls evaluate to a single value. The value that the function call evaluates to is called the return value. (In fact, we can also use the word "returns" to mean the same thing as "evaluates".) In this case, the return value of the input() function is the string that the user typed in-their name. If the user typed in Albert, the input() function call evaluates to the string 'Albert'.

The function named input() does not need any input (unlike the print() function), which is why there is nothing in between the parentheses.

- print('It is good to meet you, ' + myName)

On the last line we have a print() function again. This time, we use the plus operator (+) to concatenate the string 'It is good to meet you, ' and the string stored in the myName variable, which is the name that our user input into the program. This is how we get the program to greet us by name.

Ending the Program

Once the program executes the last line, it stops. At this point it has terminated or exited and all of the variables are forgotten by the computer, including the string we stored in myName. If you try running the program again with a different name, like Carolyn, it will think that's your name.

Hello world!

What is your name?

Carolyn

It is good to meet you, Carolyn

What is your name?

Carolyn

It is good to meet you, Carolyn

Remember, the computer only does exactly what you program it to do. In this, our first program, it is programmed to ask you for your name, let you type in a string, and then say hello and display the string you typed.

But computers are dumb. The program doesn't care if you type in your name, someone else's name, or just something dumb. You can type in anything you want and the computer will treat it the same way:

Hello world!

What is your name?

poop

It is good to meet you, poop

What is your name?

poop

It is good to meet you, poop

Variable Names

The computer doesn't care what you name your variables, but you should. Giving variables names that reflect what type of data they contain makes it easier to understand what a program does. Instead of name, we could have called this variable abrahamLincoln or nAmE. The computer will run the program the same (as long as you consistently use abrahamLincoln or nAmE).

Variable names (as well as everything else in Python) are case-sensitive. Case-sensitive means the same variable name in a different case is considered to be an entirely separate variable name. So spam, SPAM,Spam, and sPAM are considered to be four different variables in Python. They each can contain their own separate values.

It's a bad idea to have differently-cased variables in your program. If you stored your first name in the variable name and your last name in the variable NAME, it would be very confusing when you read your code weeks after you first wrote it. Did name mean first and NAME mean last, or the other way around?

If you accidentally switch the name and NAME variables, then your program will still run (that is, it won't have any syntax errors) but it will run incorrectly. This type of flaw in your code is called a bug. It is very common to accidentally make bugs in your programs while you write them. This is why it is important that the variable names you choose make sense.

It also helps to capitalize variable names if they include more than one word. If you store a string of what you had for breakfast in a variable, the variable name whatIHadForBreakfastThisMorning is much easier to read than whatihadforbreakfastthismorning. This is a convention (that is, an optional but standard way of doing things) in Python programming. (Although even better would be something simple, like todaysBreakfast. Capitalizing the first letter of each word in variable names makes the program more readable.

Summary

Now that we have learned how to deal with text, we can start making programs that the user can run and interact with. This is important because text is the main way the user and the computer will communicate with each other. The player will enter text to the program through the keyboard with the input() function. And the computer will display text on the screen when the print() function is executed.

Strings are just a different data type that we can use in our programs. We can use the + operator to concatenate strings together. Using the + operator to concatenate two strings together to form a new string is just like using the + operator to add two integers to form a new integer (the sum).

In the next chapter, we will learn more about variables so that our program will remember the text and numbers that the player enters into the program. Once we have learned how to use text, numbers, and variables, we will be ready to start creating games.

0 comments:

Post a Comment